by: James N. Gilmore

These quick thoughts are meant to offer a reflection of an idea I’ve been thinking through since spring of 2022, largely when Elon Musk first announced his intention to purchase Twitter. Now that the deal has gone through and Musk owns the company, lots of questions are circulating about leadership, staffing, the company’s future, and its ability to maintain and build a user base. Please read these as cursory, and let’s talk about them in the coming year. Things will undoubtedly continue to change.

Musk offered two Tweets as the purchase closed and he gained control of the company. In the first, he wrote, “Entering Twitter HQ – let that sink in!” This was accompanied by a 9-second video of him walking into the lobby of Twitter’s headquarters holding a white sink. The pun is something between a Dad Joke and a troll, Musk making light of a sprawling, tumultuous half-year that nearly saw him in court over his bid to purchase Twitter. In the second tweet, he wrote “Dear Twitter Advertisers,” followed by three separate screenshots explaining—to a point—his position on acquiring the company and what he saw as its future. That the letter was pitched to advertisers and not to users is telling, indicating that Musk’s first public statements on the platform are pitched at the mechanism designed to build capital. While I don’t want to walk through these statements in their entirety, I do want to point to three contrasting statements:

- “The reason I acquired Twitter is because it is important to the future of civilization to have a common digital town square, where a wide range of beliefs can be debated in a healthy manner, without resorting to violence.” This has long been a conception of contemporary social platforms—the “town square” model that owes something to Habermas’s history of the “public sphere”—but plenty of social media researchers are quick to point out the limitations of this model: As a computational software platform, Twitter simply doesn’t function this way, and the practices of trolling, disinformation, and other modes of concerted attacks mobilized through the platform undermine its possibility to really achieve this rose-colored possibility.

- “…our platform must be warm and welcoming to all, where you can choose your desired experience according to your preferences, just as you can choose, for example to see movies or play video games ranging from all ages to mature.” Theories of the active audience aside, Musk is here conflating participation in public discourse with media consumption. A choice to play a video game is quite different from choosing to voice political speech online. There have been lingering questions about Musk’s plans for content moderation and community guidelines on the platform, and this short note does nothing to address how—apart from obeying “the laws of the land” (which land, exactly?)—he understands the intricate relationship between social media and speech. It is always a productive act, not a consumptive act.

- “Fundamentally, Twitter aspires to be the most respect advertising platform in the world that strengthens your brand and grows your enterprise.” And this is, really, the main takeaway: the “town square” model is foregrounded because it sounds nice, the false analogy to movies and games only work on the most superficial level, but this is the closest Musk comes to indicating an emphasis in Twitter as a town square that works for the expressions of brands. Musk realizes that, regardless of what happens to the user base of Twitter over the coming 12-24 months, he needs to demonstrate to advertisers a commitment to the money they are willing to spend on targeted advertising, professional analytics, and reach.

So the story is the same as it ever was: The pursuit of advertisers to fund the platform and accrue value. We know this, of course; it’s the entire basis of models like Zuboff’s “Surveillance capitalism,” Smythe’s “audience commodity,” as well as any number of histories of media audience tracking and data collection—in choosing an advertising model that is “free” to use, users become the product, sold to advertisers who demand a return-on-investment and, increasingly, value granular data to understand the work of their social media brand.

But let’s talk about “value.” Because as much as Twitter’s market stock has rebounded over the course of a tumultuous year, it’s about to be taken of the NYSE. Musk’s acquisition is also taking the company private. Meanwhile, Meta—which was once seen as the biggest social network company in the world—has lost 69% of its market value over the last year. While, clearly, the stock market doesn’t tell us everything, Facebook’s rebranding into Meta has done little to build faith in the company. Earlier this month, Zuckerberg announced “legs are coming” to Meta avatars—your character in the company’s virtual reality space doesn’t exist from the waist-down—before some realized the “legs” in the hype video had been faked and created from motion capture for the purposes of the demo. It’s a small, stupid thing, but it encapsulates quite well the company’s ongoing fall from grace.

While my undergraduate students are far from a reliable sample size (about n = 50 per semester), I’ve noticed a precipitous drop in any of them saying they use Facebook and, over the last two years, any of them saying they use Twitter. Instagram and TikTok are more the platforms du jour. But with ongoing discussions about data collection and data security happening around TikTok; as Wired put it last month, “it is unclear whether TikTok poses a unique and specific threat to US national security or if it is simply a convenient proxy through which lawmakers are grappling with larger issues of data security and privacy, disinformation, content moderation, and influence in a globalized tech market.”

And this, to me, is part of what unites that Facebook now feels stale (and Meta seems unappealing to any of my students no matter how many commercials I show them), Twitter’s content moderation and speech regulations are again at the forefront as Musk promises sweeping changes to the company, and TikTok remains a sort of signifier for the perils of data privacy and security: We are at the end of the first “social media” generation.

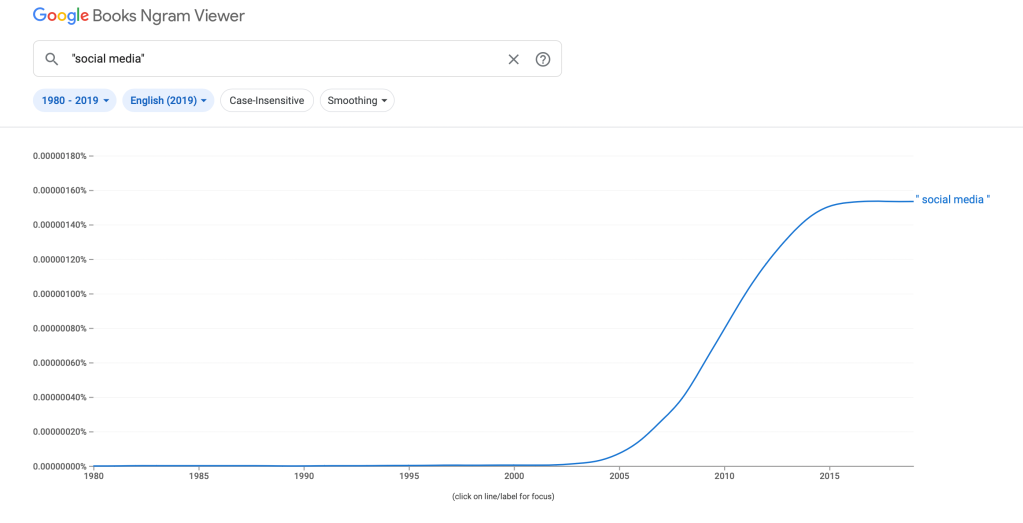

While, clearly, historians of the Internet (as well as anyone active in online networks in the 1980s and 1990s will tell you), the idea of social network websites where people could post and engage each other has been around for much longer (not to mention the arguments occasionally shared from some corners that “all media are social!”), the actual phrase social media was not meaningfully used until about 2004 according to a Google Books Ngram search:

The phrase exploded over a five-year period, coming to dominance as a fully-formed logic of technology and culture by 2010, before slowing down its discursive growth in the last decade. While an Ngram search of a word’s frequency can only tell us so much, it underscores that “social media” arrived at a particular moment. Its lasting legacy may be a recognition that all our media are inherently social, and will retain elements of social connection in future developments, but this also shows us nothing is assured here, and the history of this phrase and its dominant meanings and understandings is still very much up for grabs.

While Geocities was launched in 1994 and LiveJournal was launched in 1999, the founding of Friendster in 2002, MySpace in 2003, and Facebook in 2004 collectively inspired a sedimentation around the idea of social media as a space for online social networking and the sharing of thoughts, photos, and eventually videos.

Twenty years since the founding of Friendster, we find ourselves in a moment that will truly test the future of what the phrase “social media” is meant to indicate, and what its legacy might be. Will Facebook continue to bleed users (and fail to bring younger users into the fold), converting it into a sort of online directory of businesses and community groups? (It’s worth noting that news deserts like the one in which I live still basically only use Facebook to share community news with residents). Can Twitter survive Musk’s acquisition and his plans to center the company as a brand-focused town square? (And will news organizations and politicians continue to use Twitter, legitimating its status as this so-called “town square,” now that it’s a private company again?) As the realities of data extraction become more known and accepted, the political realities of disinformation more part of our ongoing public discussions of social media, are these forever companies? Or, to borrow a line from David Fincher’s The Social Network, has the party ended at 11? Will these companies ultimately fail to make the pivot into “The Next Generation” (Star Trek pun intended) and begin to sputter?

To be clear, I don’t think Facebook or Twitter or Instagram will disappear. They are deeply entrenched in cultural practice. But it is relatively easy, at this point, to imagine Facebook basically being an online directory, a version of the White Pages. It’s easy to imagine Twitter being basically a hub for news outlets, politicians, and public figures to share statements without much of the vibrant, chaotic (and yes, often hateful and horrid) forms of networking which characterized the platform’s first 15 year of public life.

I offer these reflections not because I have an answer, but because I think we need to encourage everyone to start thinking about these platforms as historical entities; they emerged within a particular material, cultural, economic, and technological context, and they have participated in the shifting contexts of the last 20 years. The major players in the social media industry are all at a moment of rearticulation: Formally rebranded into Meta, formally changing ownership and becoming private, these reconnections will undoubtedly spill out into other contextual relationships. Thinking of them as historically situated can give us, I hope, the necessary vantage to have serious conversations about Meta and Twitter in the coming year, as they undoubtedly undergo a series of changes to try and (re)build value.

“Social media” is a historical phrase. Its first moment of articulation shifted how different social and cultural groups engage each other, how political conversations operate, how ideologies are built and challenged, and on and on it goes. These changes are still quite deeply felt, but they are not a guarantor of any sort of future around the phrase “social media” and its broader structures of feeling. We can’t lose sight of that specific historicity as we critique the next moves of these companies and the platforms they operate.

“We are going to live on the Internet,” claims a fictional version of Sean Parker towards the end of The Social Network. But maybe that promised future has already passed, or is already passing. At the very least, life on the Internet is transforming.